The seventeenth biennial Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory meeting on the Neurobiology of Drosophila took place October 3-7, 2017. Serendipitously, the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was announced that same week and awarded to three Drosophila biologists – Jeffrey C. Hall, Michael Rosbash, and Michael W. Young – for their work in understanding circadian rhythms. We chatted with the meeting organizers Heather Broihier and Troy Littleton about fruit flies, the Nobels, and how both the meeting and the field have evolved in recent years.

Troy: This meeting, together with the European Drosophila neurobiology conference, are the only forums that bring the model system of Drosophila together with those who do neurobiology. Every other meeting in neuroscience or Drosophila either covers a broad range of topics outside of neuroscience or focuses on a variety of model systems. But we’re all tied together by the common tools we use in our field: even when people may not have a specific interest in a unique protein or a circuit, there are still common tools they’re using. There are so many ideas that happen from this meeting: it’s an excitement that brings a lot of people here.

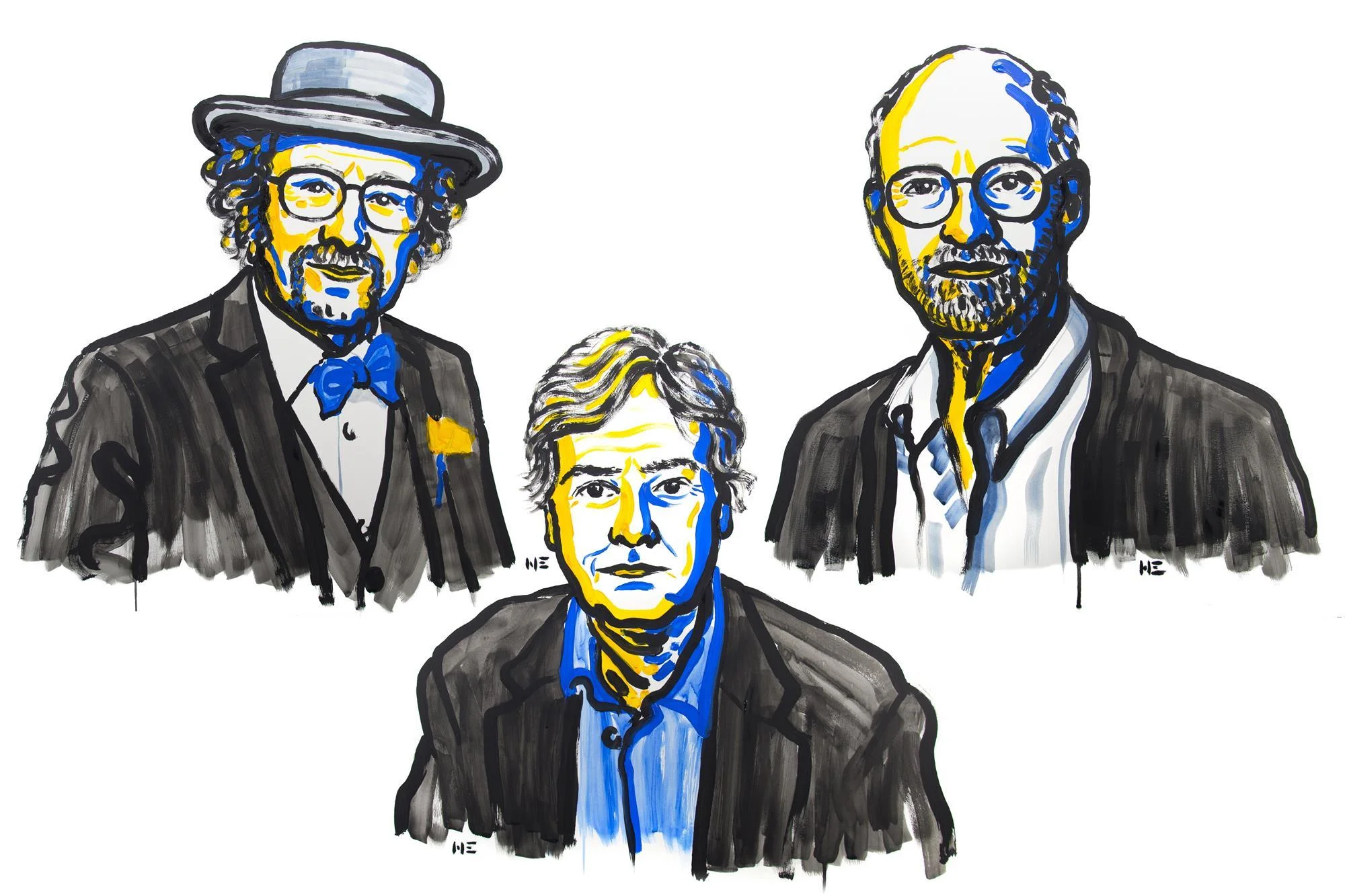

Illustration: Niklas Elmehed, Nobel Media AB 2017

Heather: This is the most exciting meeting in our field and it’s really well-represented in terms of colleagues and topics. We had about 450 participants this time representing everything from the molecular genetic level all the way up to circuits and behavior. This year’s meeting was especially exciting for us because the 2017 Nobel Prize was awarded to scientists in our field on the same day the meeting started, for work that was actually initiated in Seymour Benzer’s lab. We had a Seymour Benzer Memorial Lecture this year given by Hugo Bellen, and so everything felt timely.

Troy: One of the big excitements in our field is that we span the gap from people who study single molecules all the way up to complex behaviors mediated by the large brain circuits. Being able to see the full range of science – how single molecules make the molecular engines that ultimately allow the animals to learn and behave, and studying how that’s represented across neural circuits – is really exciting. In that regard, this is a unique meeting because those in the circuit world get to experience the molecular world and vice versa. This meeting also keeps everyone abreast of the tools across both systems that help advance both fields.

Heather: There’s been a lot of tool building, especially out of Gerry Rubin’s group in Janelia. He gave a short talk on the unbelievable pace of innovation in the computational tools we have for putting together the fly connectome in the brain —for understanding how every neuron connects at a synaptic level. For many years, the implementation of the tools wasn't quite there yet. But amazing progress has been made to enable that kind of map in what Gerry thinks will be the next five years. It’s in collaboration with Google to get through the data analysis and enable these large datasets to be connected and compiled. I’m just blown away: this kind of work was not imaginable even five years ago. The talks in the circuits session really exploded this year, and there now seems to be a huge payoff from the tool development that has gone on in our field.

Troy: Technology is a big driver in our field. In prior years, we had technology talks that were organized into small subsections and, consequently, broke the community apart. This year, we decided to have one symposium dedicated to technological developments, so everyone was in the same room and heard about the great new tools coming out. It worked really well.

Heather: We weren’t the driving force behind this, but there was also a presentation this year about the 2017 Nobel Prize. It was given by attendees who had done scientific training in each of the three labs for which the Prize was awarded. They put together a really great presentation about the history of the work that provided the students and postdocs with a more immediate sense of that history. We all felt that our entire field was awarded the Prize.

Troy: The award really emphasizes that Drosophila as a model isn’t going away anytime soon. It’s a great system to understand core principles of behavior that have been conserved across evolution. The simple fly can tell us so much about basic biology and basic mechanisms of disease that have important benefits for human health.

A unique feature of this meeting are the Elkins Memorial and Seymour Benzer lectures:

Heather: The centrality of this meeting for our field is signified by the Elkins Lecture, which is an award given every two years for the best PhD thesis in Drosophila neurobiology. Troy directs the selection committee, and the winner gives one of the full-length invited lectures here at the meeting.

Troy: This year, we had 12 or 13 nominations that were just unbelievably great. It’s always a challenge to pick from the very, very best. Ultimately the selection committee – which includes former organizers of this meeting – considers the impact of an applicant’s work in the field. The 2017 Elkins Memorial Lecture was awarded to Raphael Cohn for his work on how the fly learning centers – the mushroom bodies – encode contextual information cues from the environment. It was spectacular, beautiful work that takes advantage of all the tool development and biology available up to this point.

Heather: It’s incredibly exciting that we have such unbelievably high-quality research going on in our field. This meeting really represents the best of our community.

Troy: The Seymour Benzer keynote lecture by Hugo Bellen was another high point of the meeting for me. Hugo highlighted how the fly might inform basic mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s – i.e., the links between defects and lipid metabolism in the fly that cause neurodegeneration, and the mouse or other models with ties to Alzheimer’s. For me, the twin pillars of basic science are 1) how something not related to disease works at a fundamental level, and then 2) how to take it to a different arena to inform core disease mechanisms. Both lectures this year were excellent examples of basic science.

Organizers of Neurobiology of Drosophila hold the role for only one iteration of the meeting. Here is what Heather and Troy did in 2017 to leave their mark on the meeting:

Heather: Both Troy and I happen to be on the cellular/molecular side of the balance, so we included the meeting’s first ever Neuronal Cell Biology session. For the next iteration, the new organizers might have different interests and ways they want to highlight the strengths of our field, so it’s appropriate the organizer roles move to two different people.

Troy: It’s great to give other members of our community the opportunity to survey the field and make their own choices on what they feel are important things to bring to the meeting. Heather and I also moved the poster session to the evening and that actually turned out very well. People grabbed a beer from the bar and basically stayed as long as they wanted in the poster session.

In terms of who would benefit in attending the biennial meeting:

Troy: There are benefits across every career level. We mostly selected junior scientists to give talks, so graduate students and postdocs get to expose the community to their work. It’s a great place for younger scientists to network with more senior people. Graduate students get to “sample” and meet with people from labs they might be considering for postdocs, and the same applies to postdocs who are beginning to go in the job market. And it comes full circle: the PIs see the junior scientists present fantastic work and we can encourage them to consider our labs for future training. Personally, I'm already cherry-picking who might fit well in my home institution and encouraging them to apply for faculty positions there.

CSHL also runs an annual summer short course in Drosophila neurobiology, and a large number of course participants regularly attend the Neurobiology of Drosophila meeting. In fact, Troy was a trainee in the course in 1993 and Heather was an instructor in 2009-2011! In celebration of the course’s 30th anniversary, a reception was organized during the meeting that was attended by more than 75 course alumni dating all the way back to the Class of 1989. (Check out the complete course "class photo" gallery.)

Heather: It was an outstanding way for our community to see the importance of that course. So many of us came through the Drosophila neurobiology course as students, instructors, teaching assistants, or invited speakers, so we feel tied to it. This meeting is a great way for a lot of us to get together and see old friends.

The Neurobiology of Drosophila meeting at CSHL offers a lot to every participant. Whether one attends to discover the latest technological developments, hear a presentation on the best thesis, meet new collaborators, reunite with old friends, or celebrate the Nobel Prize with peers from the field, this meeting is, as Heather said: “THE best meeting in the field!”

The meeting returns to the Laboratory in 2019; and information on our Drosophila Neurobiology: Genes, Circuits & Behavior course can be found in this webpage. To gain an inside look into the course, be sure to read our Q&A with 2017 Course Alumnus Tayfun Tumkaya.

For more conversation with other meeting organizers, check out the rest of our A Word From series.