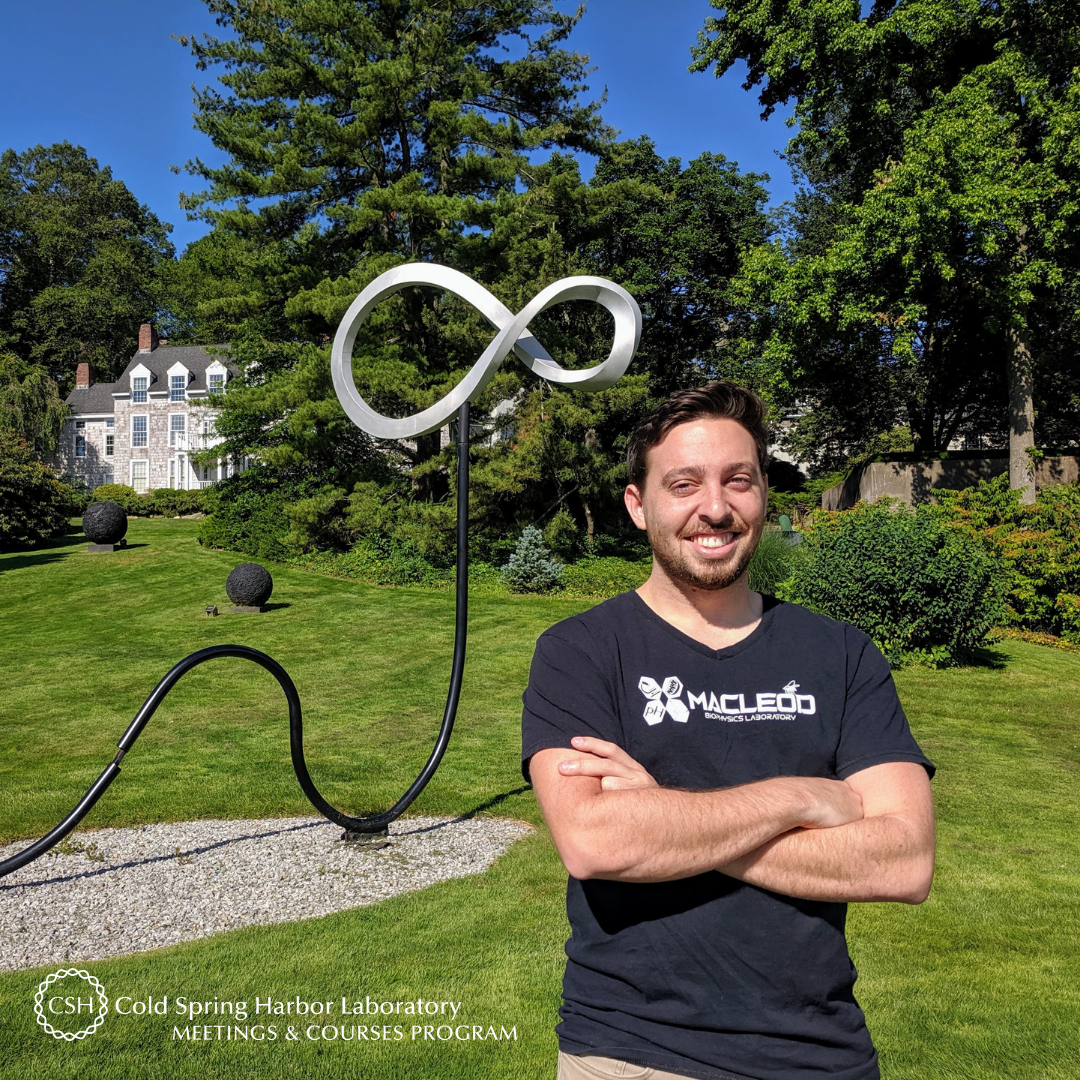

Meet Roberto Hernandez of the Florida Atlantic University. A member of Gregory Macleod’s lab, the second-year graduate student returns to CSHL for another drosophila-centric program. In 2017, Roberto took part in the Neurobiology of Drosophila meeting and is training at our Drosophila Neurobiology: Genes, Circuits & Behavior course this time around.

What are your research interests? What are you working on?

I am currently investigating how neuronal pH changes during synaptic activity and the impact these changes have on neurotransmission.

How did you decide to make this the focus of your research?

I became interested in this topic while helping Michal Stawarski collect neurophysiological data while disturbing pH homeostasis during neurotransmission. This project drove me to question how many untreatable neurological disorders may be related to pH imbalance in the central nervous system. However, the lack of research on pH dynamics in neurons and its effects on neurotransmission makes it difficult to venture into this topic. But this didn’t stop me. The lack of information and unique challenges presented by this project gave me an inexplicable sense and passion to discover the unknown as well as provide others with some insight into this field.

How did your scientific journey begin?

The application of scientific knowledge to understand how humans and the world functions has always been a source of wonder to me. Inspired by the many scientific documentaries I have watched and the ambition to one day either make a discovery or treat individuals led me to pursue a career in the STEM field. There was a point in time when I aspired to become a medical doctor specializing in neurology and scientific research was nowhere on my radar. My organic chemistry professor at Miami Dade College, Dr. Carlos Fernandez introduced me to scientific research and had often hinted that the qualities I possess were that of a scientist. Upon graduating with an A.A., I moved to the Harriet L. Wilkes Honors College of Florida Atlantic University and was still very much interested in the medical tract. However, I became more curious about research and joined Dr. Gregory Macleod’s lab which was where I grew to further appreciate scientific research, found a deep passion for neuroscience, and decided to pursue a PhD in Integrative Biology-Neuroscience.

Was there something specific about the Drosophila Neurobiology course that drew you to apply?

I found the Drosophila Neurobiology course of interest because the lab techniques it covers will take my current skill set to the next level and see me through my PhD and scientific career. Further, this course provides me with the unique opportunity to learn about the ongoing research in the Drosophila community and network with the students also attending the courses.

What and/or how will you apply what you’ve learned from the course to your work?

This course provides many benefits for unraveling disruptions to the anatomy and physiology of the fly. Being trained in high-speed fluorescent imaging, immunohistochemistry, and electrophysiology will enable me to assess differences in signaling mechanisms or structures as well as elucidate distinct neurophysiological phenotypes caused by acid-base imbalances. Learning the proper methods of studying specific behaviors will help me to determine how the mutation is affecting the memory and motor functions of the fly, linking a molecular phenotype to a behavioral response. I hope to apply these skills to investigate genetic mutations that disrupt acid-base homeostasis during neurotransmission (a concept poorly researched to date) by transferring such mutations to Drosophila via CRISPR in conjunction with other molecular techniques.

What is your key takeaway from the course?

The different perspectives and approaches of application that are available to my research.

If someone curious in attending this course asked you for feedback or advice on it, what would you tell him/her?

This course is phenomenal; the techniques you will learn are valuable in neuroscience and required for any lab using Drosophila as a model organism. Further, you get the rare opportunity of learning taught these techniques from the best scientists in the field. Also important is the opportunity to make connections with others within the field, connecting you to the greater Drosophila community.

What do you like most about your time at CSHL?

What I like most about my time at CSHL is the opportunity I have in making friendships with fellow course members and network with guest speakers.

Roberto received a scholarship from the International Brain Research Organization (IBRO) to cover a portion of his course tuition. On behalf of Roberto, thank you to IBRO for supporting and enabling our young scientists to attend a CSHL course where they expand their skills, knowledge, and network.

Thank you to Roberto for being this week's featured visitor. To meet other featured scientists - and discover the wide range of science that takes part in a CSHL meeting or course - go here.