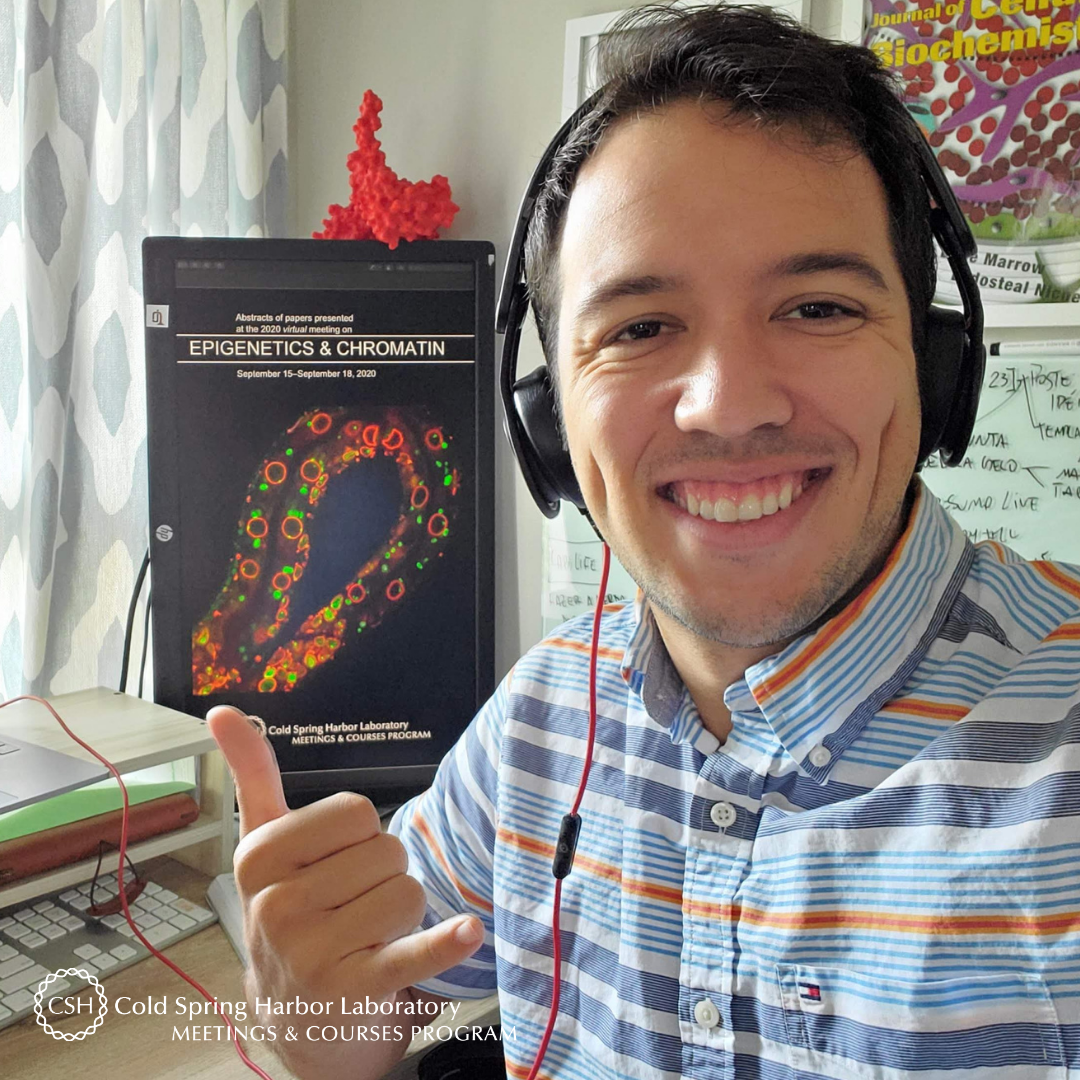

Meet Temitope “Temi” Adebambo of Emory University. The Nigerian citizen is a postdoctoral fellow and member of Dorothy Lerit’s lab. He is participating in the Quantitative Imaging: From Acquisition to Analysis (QICM) – his first course at CSHL and since the pandemic. Temi shared that “there is [a] healing side to having a program in person” and we could not agree more.

Tell us about your research.

My research is focused on how toxins affect development using Drosophila as a model organism. I am also interested in the roles played by centrosome in regulating cell cycle and how this affect the neurobiology of flies.

How did you decide to focus on this area/project?

Trained as a toxicologist, my Ph.D. demonstrated the global effect of low molecular weight aromatics in flies using genome-wide techniques and linking this to cell cycle defects in mitotically active imaginal wing disc.

What and/or who is the inspiration behind your scientific journey?

Prof. Adebayo Otitoloju, my undergrad/Masters/Ph.D. degrees mentor has been an excellent inspiration for my scientific journey.

What impact do you hope to make through your work?

Teaching and research is my thing and I want to do so much research, acquire relevant training in order to provide meaningful mentorship for the next generation of researchers.

What do you love most about being a researcher?

No time spent in conducting research is ever wasted, there is always a lesson to be learnt.

What drew you to apply to this course?

To be a better researcher but most importantly to help me better settle into cell biology.

What is your key takeaway from the Course; and how do you plan to apply it to your work?

Important microscopic techniques that were learned by accident or by necessity in a haste are no longer so. I have a better knowledge of the behind-the-scene operations of these techniques and how to tailor them to my research interests. From Brightfield to TIRF microscopes and Deep machine learning, I now have the right combination of tools to advance my research.

What feedback or advice would you share with someone considering to participate in this course?

If you think you know microscopy, you don’t.

What’s the most memorable thing that happened during the Course?

I have never seen a live cell imaging system before--that is forever memorable.

What do you like most about your time at CSHL?

I don’t have to worry about food; I don’t have to cook and there is absolutely no need to rely on any transport system as everything is in one location. Whoever came up with the idea to have a discussion every morning before lectures and the little break in between lectures is a genius. Those are always very helpful.

Thank you to Temi for being this week's featured visitor. To meet other featured researchers - and discover the wide range of science that takes part in a CSHL meeting or course - go here.

Image provided by Temitope Adebambo