Last year, we hosted the now-annual summer course on the Cellular Biology of Addiction. The formerly biennial course was started by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 2001 and in 2014, it was introduced in Europe to serve and train researchers based in European and African countries. During odd-numbered years, the course is held at the Banbury Conference Center of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and in even-numbered years, it’s at Gonville & Caius College in the University of Cambridge. We sat down with instructors David Belin, Antonello Bonci, Christopher Evans, and Brigitte Kieffer to chat about the course and the changes it’s undergone over the last 16 years. Our conversation began with an overview on the day-to-day life of a Cellular Biology of Addiction trainee:

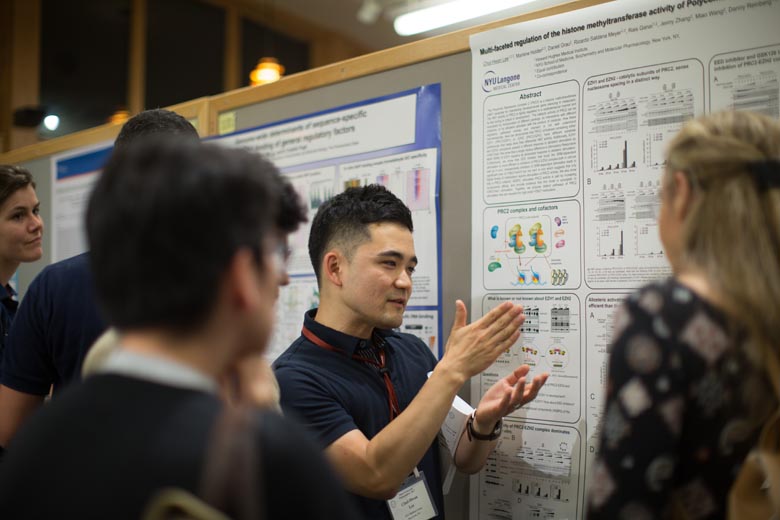

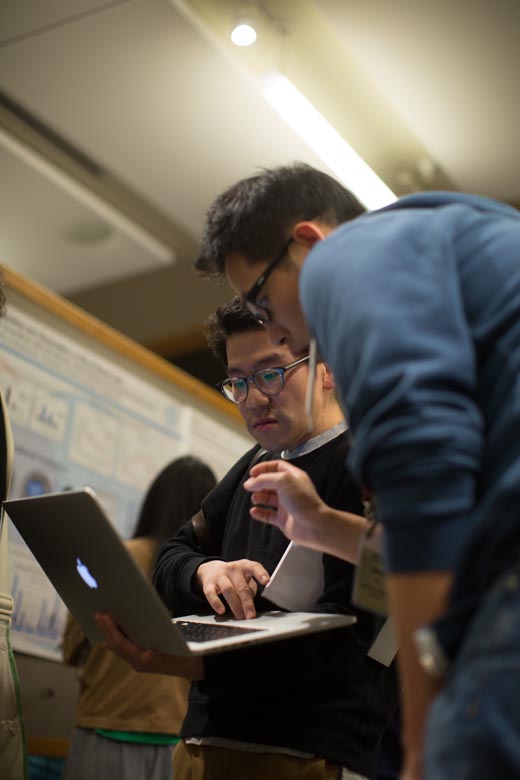

Christopher: Each day begins with breakfast where we, along with the lecturers, eat and chat with the trainees about topics ranging from science to their careers. Then we head to the Conference Center and listen to the first lecture of the day, where there are a lot of questions and discussions. Often, trainees will ask “How did you do that in that experiment?” or “Can I get a copy of your poster which shows how this works?” After a break, we’ll have another lecture before lunch, which has the same format as breakfast: everyone chats, asks questions, and maybe discusses a specific topic which came up during the talks. The afternoons are variable because sometimes we have another lecturer or two, sometimes the trainees present their work, sometimes we’ll have a pool party, etc.

Antonello: But the constant is that there’s nonstop interaction – during a lecture, pool party, dinner, or after dinner we are always together.

David: The trainees also present data themselves during one afternoon of the course. It’s kind of like speed dating for presentations. Each trainee has three minutes to convey what they’re doing and the prospective outcomes of their work, and then we have a five-minute group discussion.

Also fairly new to the course is the grant writing workshop. Each of the faculty design a call for proposals, like a five-year grant for $2 million on optogenetic control in addiction. The trainees team up, choose a call and, within 90 minutes come up with a proposal idea they need to defend. We carry this out as a game and score their performance as a group on issues like feasibility and timelines, with the goal of getting everyone involved and learning from each other. The team that performs best receives a bottle of champagne, which we often drink together.

This itinerary wasn’t always the norm. In fact, a typical day during the early years of the course was so packed with lectures and information that it left little time for participants to digest and appreciate the knowledge they’d learned or the people they’d met:

Christopher: In 2001, when I first joined the course, it was much more intensive on lectures – it was just about information. It’s evolved now so there’s much more time for discussions and interactions.

Brigitte: Originally, there were about 4 speakers per day and each speaker had 2 sessions. So we had talks all day – it was very intense.

Christopher: It was too intense. The trainees needed time to digest and meet with faculty. As the course evolved, we also folded in things like grant writing and other tools to help the next generation succeed as independent researchers.

Antonello: Basically, the course has become more career-focused to give participants all the possible information and options that we can. It’s much more long-term now, about their futures.

Christopher: Also we now have a rule where the trainees are the first ones to ask a question during invited talks. Lots of course faculty always want to ask questions but we make them wait.

Antonello: The questions from trainees are awesome.

Christopher: Absolutely. We encourage them right from the beginning of the course to express themselves and ask what they need.

David: Hopefully, one day, the faculty will be intimidated when they come for the course. That’s our aim: for the trainees to make them sweat, to squeeze their brains. It happened to me last year. One of the trainees gave an incredible presentation that blew my mind and I was just like, “Whoa, she’s better than me.” She’s now an invited speaker – someone who was a trainee last year is a speaker this year. And that’s beautiful. The course is dynamic and flexible, it’s open to new ideas and new people.

Antonello: We had another lecturer this year who had prepared about a hundred slides for her two-hour talk. She reached slide number 6 because the trainees asked questions non-stop. So that gives a glimpse of their level of excitement and curiosity.

Brigitte: Yes. The course is interactive, all the time. And every year, we have pretty young investigators as invited speakers which is very important, because they’re the role models for trainees, the examples.

We switched topics to discuss the developments they’re most excited about. Technological advances were at the heart of this discussion and they all agreed that, even as new technologies become available and bridge gaps, it’s important to remember that they’re just tools.

David: There are new developments on every front, every month that are all exciting. Most of the new breakthroughs are technological, though I don’t want the next generation in addiction research to be technology driven; that’s something we try to convey in the course. Over the last couple of years, I’ve seen many papers re-inventing the wheel, re-describing something we’ve known for 50 years but with a new technique. I’m not sure that adds much to the overall picture.

Antonello: David touched on something very important. This generation of scientists is exposed to a plethora of new techniques almost on a monthly basis. These are amazing techniques. The problem is that it is easy to confuse how much novelty you can gain from a new technique, versus how much you can gain by creating a hypothesis and then using the new technique to answer your hypothesis. This seems obvious to us but it’s sometimes not obvious to younger scientists, so we always need to clarify that technology, per se, is a tool. It’s not the end goal of research because you use technology to answer questions. I think David is right in that sometimes a new technology allows you to quickly create papers but not necessarily…

Christopher: Change the field.

Antonello: Exactly…change the field. Though admittedly, technologies created in the last few years have, in my experience, created something wonderful: basic scientists and clinicians have become much closer than before. I’m referring to optogenetics and chemogenetics , techniques that turn on and off big portions of your brain. These technologies have been used to launch ideas toward the clinic where you have a variety of brain stimulation techniques. The techniques used in rodents to decode behaviors and symptoms, and those used in humans to decode behaviors and treat symptoms, are getting closer and closer, to a point where communication between basic scientists and clinicians is beginning to level. It has made basic research much more accessible to clinicians and that’s a big plus.

Brigitte: I agree completely. We have to be careful about technology being the driver, but I like to remember that technology development allows science to progress to new concepts, ideas, discoveries, to things we didn’t know and didn’t even think about. So it’s always a trade-off between progressing the technology and then progressing the biology. But of course, for young scientists, it is more difficult to step back and differentiate the two aspects.

David: We still don’t understand exactly how we see images, contrasts, shapes, etc. We know how we perceive, but we don’t know how we have a subjective image in our head that is a reconstruction of the perception we have of the world. When you accept that, you understand that that we don’t really know why we want, or how we want, or how it goes wrong – and in addiction something goes wrong, Technology helps to bridge that gap but what’s exciting is that there’s still a gap.

Brigitte: We really don’t completely grasp brain function, how the brain functions as a whole, and that’s exciting. It’s not like the kidney. I have nothing against kidneys or livers but the brain has several additional dimensions that are fascinating.

Christopher: In the course we encourage all approaches, from molecular and genetics all the way to behavior. It’s great to have new techniques but you have to use them to add to the big picture. The course isn’t focused on just molecular and cellular studies anymore, like it used to be. We should really change the name to something like “Biology of Addiction” or “Addiction Science.”

We next asked how they select course trainees from the applicant pool. To those applying for this course, be sure to craft a compelling personal statement!

David: I have always found the selection process to be difficult for a number of reasons. First of all, almost every single application is outstanding. And secondly, we’re trying to actually figure a person’s career trajectory, and whether that person will benefit more from the course than somebody else within this trajectory. It’s a best guess, right? I literally spent five days reviewing the applications for this year’s course. I guess it’s a hallmark of the success of the course: very good people apply.

Put effort into the [personal statement]. Applications that appeal to my heart are the ones with beautiful [personal statements], where the applicant tells me why they want to come to the course and why they want to come now. I rank a bit poorly the applications that clearly display a mismatch between the quality of the CV and the effort put into writing the [personal statement]. It comes off as if the applicant considers their CV to be good enough to deserve selection.

Antonello: It’s a good point. The [personal statement] is the only way an applicant can show they care about this course.

Christopher: For me, it is the reference letters that make the difference. Applicants should choose people who really know them, and not just get a big name in the field to write down a few words.

We ended our chat by asking them to share their favorite moment from the course so far:

Christopher: Swimming in the phosphorescence. A trainee had found something with GFP overexpression in D1 and D2 cells, and they were anxious to talk about it because it ran counter to what big shots in the field thought should happen. We helped the trainee deal with that. Established people in the field often have their set ideas, and it can be intimidating for a new scientist to present a discovery that is not in line with their thinking. We help our students develop the strength of character to deal with these situations in the field. I like to see things change, people change. The students always ask good, very insightful questions that other people haven’t thought of.

Brigitte: The lectures are a very, very good time. The trainees’ questions are very bright, intelligent, and well-thought out.

Christopher: Yeah, we get a lot from this course as well. There’s no two ways about it. We learn a lot.

Antonello: The beauty of this course is that each one of us brings a very different contribution to the same painting.

The Cellular Biology of Addiction course this summer will take place between July 29th and August 5th in Cambridge, UK. Applications are being accepted until this Sunday, April 15th here. For an introduction into the course, be sure to read our Q&A with 2017 Cellular Biology of Addiction Alumna Sadie Nennig and watch videos of the talks from the 2014 course.

For more conversation with other meeting organizers, check out the rest of our A Word From series.